To advance equitable access to speech technology, a team from the Centre for Digital Language Inclusion (CDLI) under the Global Disability Innovation Hub at the University College of London paid a visit to the Responsible AI Lab (RAIL) at the KNUST Engineering Education Project (KEEP), where they engaged researchers, faculty, and students of the lab in an exploration of how artificial intelligence, speech recognition, and inclusive technology can transform access for individuals with non-standard speech, particularly across African contexts.

The team included Prof. Catherine Holloway, Academic Director and Co-founder of the Global Disability Innovation Hub and co-founder of CDLI; Dr. Richard Cave, a speech and language therapist and sub-programme lead of CDLI; and Katrin Tomanek, a former staff software Engineer at Google and technical Lead AI and Voice Technology at CDLI, whose work has focused extensively on making Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) work for people with different speech patterns.

The engagement began with Prof. Jerry John Kponyo, Principal Investigator and Scientific Director of RAIL and Project Lead for KEEP, who welcomed the CDLI team and outlined the vision behind RAIL, which is dedicated to responsible, inclusive, and impactful AI solutions. He explained how KEEP was designed to deliver quality engineering education without necessitating brain drain, a response to the pattern of African scholars studying abroad and not returning “We’ve spent years sending our best minds abroad. Often, they don’t return. The idea behind KEEP is to build an environment where the same quality of education and innovation can happen here,” he said.

CDLI’s team opened their session by presenting the global problem they aim to address: the systemic exclusion of people with non-standard speech from mainstream speech technology platforms. Dr. Richard Cave highlighted that as many as 250 million people worldwide have speech that is hard for people and AI systems to understand, and this is as a result of disabilities such as cerebral palsy, Parkinson’s, ALS, stroke, or head and neck cancer.

“These individuals often face social isolation, loss of independence, and discrimination, not because of cognitive limitations, but because their voices are not recognised by the systems that mediate modern life,” he said.

The team detailed their work on Project Euphonia, a Google Research initiative focused on building ASR systems for impaired or non-standard speech. Prof Catherine Holloway explained how the project began with data collection, centred on use cases such as smart home control and caregiver communication, eventually expanding into conversational AI as users naturally wanted to talk beyond commands.

“With contributions from hundreds of participants, the project has generated the world’s largest dataset of non-standard English speech, over 2,000 hours, spanning a broad range of speech impairments”, she said.

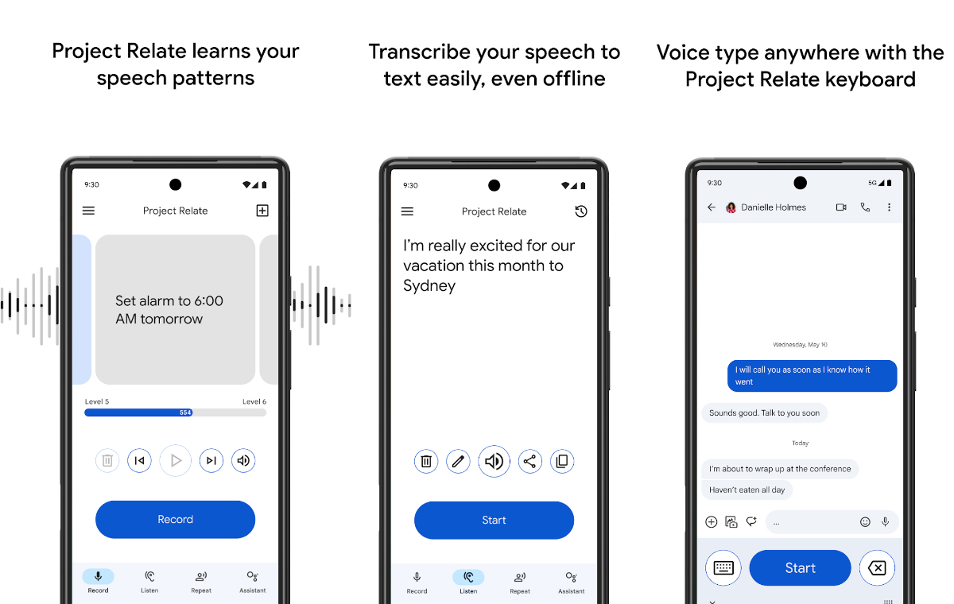

This work culminated in developing Project Relate, an Android app that offers real-time transcription, speech clarification, and communication support for users with impaired speech.

Dr. Cave described the question that brought the CDLI team to Ghana: Would Project Relate work here? They conducted a six-week pilot study in Accra and Tamale to answer that. Working with Ghanaian speech and language therapists (SLTs), the team trained 20 adults with speech impairments to use the app.

In a documentary, one participant, Adwoa, a human rights lawyer with cerebral palsy, spoke about being denied access to courtrooms due to her speech. She is regaining her professional footing with Project Relate, thanks to a tool that improves her confidence and supports communication.

Another standout story was Radiat, a university student in Tamale and the first in her family to attend higher education. With cerebral palsy, she not only uses the technology herself but is now setting up a foundation to mentor younger students with disabilities, encouraging their families to embrace education and reject stigma.

Katrin explained the technical side of adapting ASR for African contexts, particularly the challenges of working with local languages like Akan, Ga, and Dagbani. They emphasised the difficulty of transcription when few people can read or write the language, and when dialectal variation creates inconsistencies. Katrin explained that identical Word Error Rates across models do not guarantee equivalent understanding or meaning preservation. “To address this, they are testing large language models (LLMs) capable of assessing whether the intended meaning is preserved, and a more accurate reflection of real communication success,” she said.

Another limitation was that the Project Relate app, originally designed for English, required Ghanaian users to adjust their speech to Americanized patterns. It failed to recognise common cultural terms like jollof rice or fufu, forcing users to input such terms manually. This is an unfair burden, particularly for users with limited dexterity or literacy. The team also discussed plans to integrate speech synthesis, particularly for individuals who cannot read or write, to enable speech-in, speech-out communication tools in local languages and dialects. Combined with speech recognition, these tools could revolutionise communication for people with speech challenges.

The CDLI team reaffirmed their commitment to open-source development and local ownership throughout the meeting. They announced that all training scripts, toolkits, and data pipelines developed will be made publicly accessible. A key principle emphasised was that all data collected in Ghana remains within the country, with full ownership retained by local institutions. This approach aims to empower local innovation teams to adapt and extend these tools for their specific community needs and also hopes to gather more data.

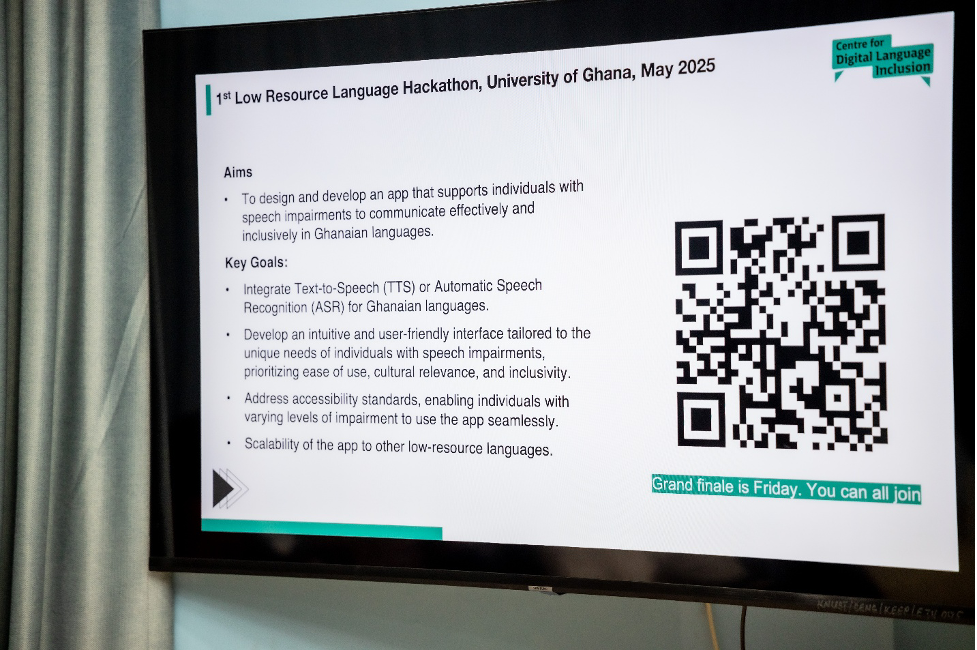

Currently, CDLI is working with the University of Ghana on a hackathon centred on training Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) models using 100 hours of Akan speech data, primarily recorded from speakers with speech impairments.

Prof. Kponyo closed the session by emphasising the strategic alignment between CDLI’s mission and RAIL’s vision for responsible AI. The meeting concluded with a consensus to establish a dedicated working group from RAIL to formalise collaboration and advance joint projects. “What inspires me is changing lives,” he said. “It’s frustrating when someone can’t be understood. If we can make that easier, then it’s worth everything”, he said